Le Lieutenant-Colonel de Maumort

Le roman du colonel de Maumort est une œuvre monumentale, Martin du Gard y a travaillé de 1941 à sa mort, en 1958. Il pressentait qu'elle serait posthume, mais il en souhaitait la publication. Son héros, Maumort, né en 1870, passe sa jeunesse à la campagne, dans le Perche. Ensuite, à Paris, il est hébergé par un oncle qui fréquente tout ce que l'Université et l'Institut comptent de grands hommes : Renan, Leconte de Lisle, Berthelot. Il participe à la conquête du Maroc, fait la guerre de 1914-1918, et organise la Résistance dans le Lot pendant l'Occupation.

Durant toute sa vie, Maumort tient des carnets, un journal. Après une attaque, sa vie devient intenable, et il envisage le suicide.

On retrouve le Martin du Gard des Thibault, avec son don de créer des personnages auxquels on s'attache. Pour la première fois, il aborde avec une liberté complète les problèmes de la sexualité, et notamment ceux de l'homosexualité. Une des grandes idées du roman est que tout homme a deux vies, sa vie sociale et sa vie secrète. Faute de connaître la seconde, on ne connaît généralement pas les gens, même les plus proches. -Gallimard-

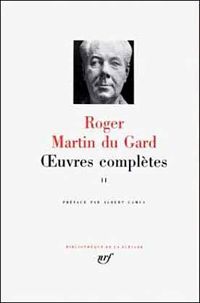

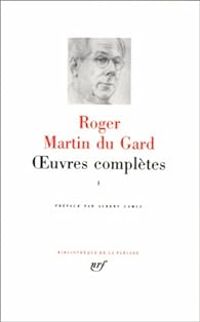

Roger Martin du Gard is a member of a small, fairly exclusive club: obscurities who have won the Nobel Prize. The French author, who switched from paleography to fiction in his early 20s, was awarded literature's ultimate gold star in 1937, largely on the strength of a multivolume family saga called The Thibaults. But du Gard's magnum opus, which he was still working on when he died in 1958, is Lieutenant-Colonel de Maumort. This unfinished epic presents itself as the fictional memoir of the eponymous colonel, who is born into privilege in 1870 and dies some 80 years later, having only intermittently achieved the sort of honor he craves. Weighing in at nearly 800 pages, Maumort's story is an exhaustively detailed portrait of the class that shielded him, the women who tempted him, the teachers who influenced him, and--last but not least--the desires that overcame him. For readers familiar with the period and place, this is an invaluable document. For others, Maumort's "memoir" offers more formidable challenges: charged up with Proustian ambitions, du Gard has none of Proust's poetry or hypnotic grace. To put it another way, Proust wrote as if he were holding back a flood, while Maumort's creator seems rigidly in control at all times: It was quite foolish of me, when I began, to want to get away from chronological order. I imagined that this constraint might spoil my pleasure. This showed a poor knowledge of myself. I have too much rigor in my brain to escape from logical order, and it is in their historical sequence that past events quite naturally come back into my mind. Which, besides, does not in any way imply that I henceforth deny myself unchronological digressions. No set positions, no preconceived discipline: I let my pen run on according to the wishes of my fancy. But the fancy of an old rationalist is less capricious than I had imagined... To be sure, the old rationalist does have his charms. But by part 4, the book begins to fall apart, hovering between form and formlessness in a manner that's (unintentionally) quite interesting. Clearly du Gard intended for the narrative to shift as Maumort grew older--but he was growing older too, and running out of time. In the end both the author and his creation fade out into an assemblage of notes, shorthand episodes, and supplementary meditations. As du Gard himself wrote of Lieutenant-Colonel de Maumort, "It is a work that can grow and be perfected indefinitely: a work that will never be finished for me, and that, however, may at any moment be interrupted by my death." Here, perhaps, lies the novel's ultimate pathos: both the hero and the text strive after eternity, but are always utterly dependent on the transitory world. --Emily White